Obviously we can only approach such total perspective; to possess it would be to be God. The first lesson of philosophy is that philosophy is the study of any part of experience in the light of our whole experience; the second lesson is that the philosopher is a very small part in a very large whole. Just as philosopher means not a “possessor” but a “lover” of wisdom, so we can only seek wisdom devotedly, like a lover fated, as on Keats’ Grecian urn, never to possess, but only to desire. Perhaps it is more blessed to desire than to possess.

Shall we have examples? Rain falls; you mourn that your tennis games must be postponed; you are not a philosopher. But you console yourself with the thought, “How grateful the parched earth will be for the rain!” You have seen the event in a larger perspective, and you are beginning to approach wisdom.

You may be a young radical, or an old businessman crying out for limitless liberty, and as such you may be a useful ferment in a lethargic mass; but if you think of yourself as part of a group, and recognize morality as the cooperation of the part with the whole, you are approaching perspective and wisdom. You may be a politician just elected to Congress for a term of two years; you spend half your time planning re-election; the situation encourages a myopic perspective, contracepting wisdom. Or you may be a secretary of state, or a president, seeking a policy that will protect and improve your country for generations; this is the larger perspective that distinguishes the statesmen.

Or you may be an Ashoka, a Marcus Aurelius, or a Charlemange planning to help humanity rather than merely your own country; you will then be a philosopher-king.

I have in my home a picture of the Virgin nursing her Child with St. Bernard looking at the Child. Your first thought may be that he is looking in the wrong direction; you are not a philosopher. Or you may remember Bernard as the persecutor who hounded Abelard from trial to tribulation until only the philosopher’s bones were handed to Heloise; and you vision for a moment the long struggle of the human mind for freedom; you are seeing the picture in a larger perspective; you touch the skirts of wisdom.

Or, again, you see the mother and her child as a symbol of that vast Amazon of births and deaths and births that is the engulfing river of history; you see woman as the main stream of life, the male as a minor commissary tributary; you see the family as far more basic than the state, and love as wiser than wisdom; perhaps then you are wise.

In a total perspective, all evil is seen as subjective, the misfortune of one self or part; we cannot say whether it is evil for the group, or for humanity, or for life. After all, the mosquito does not think it a tragedy that you should be bitten by a mosquito. It may be painful for a man to die for his country, but Horace, safe on his Sabine farm, thought it very dulce et decorum — that is, very fitting and beautiful.

Even death may be a boon to life, replacing the old and exhausted form with one young and fresh; who knows but death may be the greatest invention that life has ever made? The death of the part is the life of the whole, as in the changing cells of our flesh. We cannot sit in judgment upon the world by asking how well it conforms to the pleasure of a moment, or to the good of one individual, or one species, or one star. How small our categories of pessimism and optimism seem when placed against the perspective of the sky!

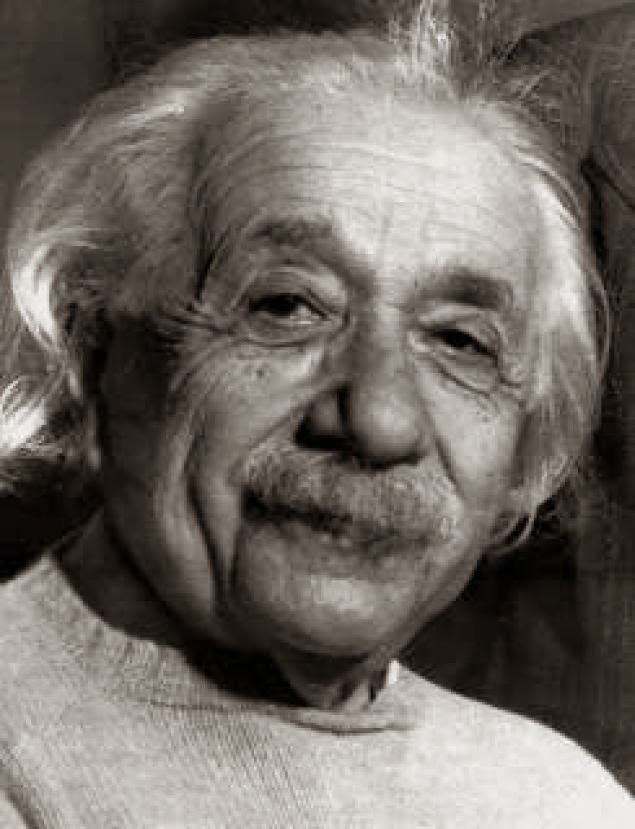

Are there any special ways of acquiring a large perspective? Yes. First, by living perceptively; so the farmer, faced with a fateful immensity day after day, may become patient and wise. Secondly, by studying things in space through science; partly in this way Einstein became wise. Thirdly, by studying events in time through history. “May my son study history,” said Napoleon, “for it is the only true philosophy, the only true psychology;” thereby we learn both the nature and the possibilities of man. The past is not dead; it is the sum of the factors operating in the present. The present is the past rolled up into a moment for action; the past is the present unraveled in history for our understanding.

Therefore invite the great men of the past into your homes. Put their works or lives on your shelves as books, their architecture, sculpture, and painting on your walls as pictures; let them play their music for you. Attune your ears to Bach, Vivaldi, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Berlioz, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Rachmaninoff, Chopin, Brahms, Debussy. Make room in your rooms for Confucius, Buddha, Plato, Euripides, Lucretius, Christ, Seneca, Montaigne, Marcus Aurelius, Heloise, Shakespeare, Bacon, Spinoza, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Gibbon, Goethe, Shelley, Keats, Heine, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Spengler, Anatole France, Albert Schweitzer. Let these men be your comrades, your bedfellows; give them half an hour each day; slowly they will share in remaking you to perspective, tolerance, wisdom, and a more avid love of a deepened life.

Don’t think of these men as dead; they will be alive hundreds of years after I shall be dead. They live in a magic City of God, peopled by all the geniuses — the great statesmen, poets, artists, philosophers, women, lovers, saints — whom humanity keeps alive in its memory.

Plato is there, leading his students through geometry to philosophy; Spinoza is there, polishing his lenses, inhaling dust and exhaling wisdom; Goethe is there, thirsting like Faust for knowledge and loveliness, and falling in love at seventy-three; Mendelssohn is there, teaching Goethe to savor Beethoven; Shelley is there, with peanuts in one pocket and raisins in the other and content with them as a well-balanced meal; they are all there in that amazing treasure house of our race, that veritable Fort Knox of wisdom and beauty; patiently there they wait for you.

Be bold, young lovers of wisdom, and enter with open hands and minds the City of God

Will Durant